You can see the original review at http://www.nudgemenow.com/article/person-sheila-heti/

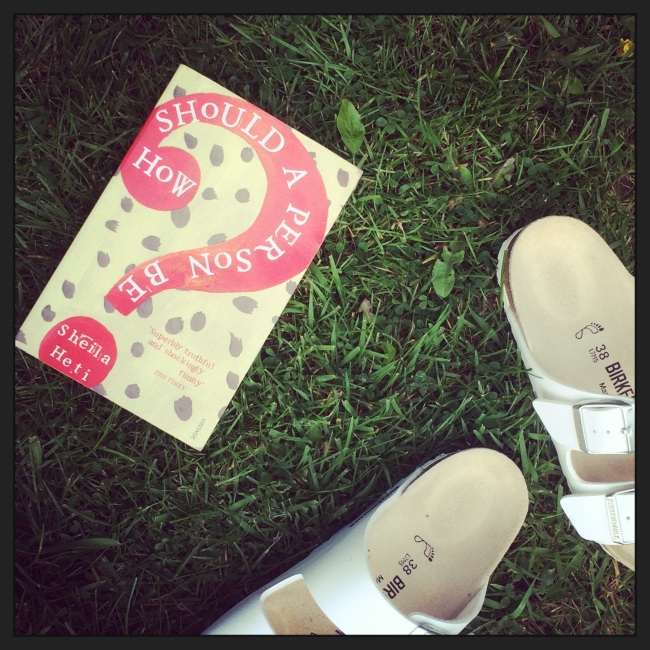

It’s been three days since I finished How Should a Person Be? and I’m still not sure how I feel about it. Like a modern-day On the Road, it’s sprawling and playful, expressing the hopefulness, creativity and uncertainty of today’s urban twenty and thirty-somethings. I’m not sure it’s great writing. But does it matter?

Heti’s book is a tapestry of different forms, a fictionalised account of real life. Into a first-person narrative she weaves emails between her and her friends and transcripts of their long, meandering musings on life and art. Within the book, other art forms are being created and dissected, from the play Heti is struggling to write to the art work created by her close friend, Margaux Williamson. It’s a book that asks whether telling a story through art or literature can ever bring meaning to your own life; make you feel more anchored in the world.

It’s also about how we position ourselves, and shape our perception of the world, through our social circles. Heti and her friends, all artists of some kind, are like flints and steel rubbing together, trying to create a spark. The transcripts of their rambling conversations appear unedited (although this may not be the case) and Heti illuminates a wonderfully messy and vibrant world, which occasionally yields what seem to be life-changing moments. There are drugs – “when we took them, we expanded into a thousand pieces” – and there are drunken revelations: “The bar around us became rich and saturated with colour, as if all the molecules in the air were bursting their seams.” However, Heti undercuts this idealism with a wry humour, and often these experiments and encounters turn out to be dead ends. She is particularly scathing about the well-meaning men she meets: encounters which often start off positively but conclude with her realising, with disappointment, that “he was just another man who wanted to teach me something.”

The patchwork approach of the novel reflects Heti’s own chaotic attempts to find direction: as her psychiatrist warns her, “it is the everlasting switching that is the dangerous thing, not what [you] choose.” This would have been an apt warning for the book itself, which is messy and unconventional, sprawling and unconstrained. It can be joyous and bright, but at times it is frustrating and insubstantial, like eating air. The circular conversations are funny to a point, and yes, the characters know their own narcissism only too well – but the plot goes so round and round, so centred in someone’s head, that it makes you feel dizzy; it’s like being carried along in the clouds, desperately grasping for solid ground.

Like Heti – or, at least, her character within the book – How Should a Person Be? tries to do and say too much. It’s a play within a book, it’s Sheila but not really Sheila, some of it really happened and some didn’t; it’s a book about her and it’s a book about all of us. It’s an experience to read, it’s perceptive, it reflects what it’s like to be endlessly searching to make sense of your presence in the world. It’s often invigorating but also infuriating and, like its characters, lacks any real sense of purpose.

It’s been three days since I finished How Should a Person Be? and I’m still not sure how I feel about it. Like a modern-day On the Road, it’s sprawling and playful, expressing the hopefulness, creativity and uncertainty of today’s urban twenty and thirty-somethings. I’m not sure it’s great writing. But does it matter?

Heti’s book is a tapestry of different forms, a fictionalised account of real life. Into a first-person narrative she weaves emails between her and her friends and transcripts of their long, meandering musings on life and art. Within the book, other art forms are being created and dissected, from the play Heti is struggling to write to the art work created by her close friend, Margaux Williamson. It’s a book that asks whether telling a story through art or literature can ever bring meaning to your own life; make you feel more anchored in the world.

It’s also about how we position ourselves, and shape our perception of the world, through our social circles. Heti and her friends, all artists of some kind, are like flints and steel rubbing together, trying to create a spark. The transcripts of their rambling conversations appear unedited (although this may not be the case) and Heti illuminates a wonderfully messy and vibrant world, which occasionally yields what seem to be life-changing moments. There are drugs – “when we took them, we expanded into a thousand pieces” – and there are drunken revelations: “The bar around us became rich and saturated with colour, as if all the molecules in the air were bursting their seams.” However, Heti undercuts this idealism with a wry humour, and often these experiments and encounters turn out to be dead ends. She is particularly scathing about the well-meaning men she meets: encounters which often start off positively but conclude with her realising, with disappointment, that “he was just another man who wanted to teach me something.”

The patchwork approach of the novel reflects Heti’s own chaotic attempts to find direction: as her psychiatrist warns her, “it is the everlasting switching that is the dangerous thing, not what [you] choose.” This would have been an apt warning for the book itself, which is messy and unconventional, sprawling and unconstrained. It can be joyous and bright, but at times it is frustrating and insubstantial, like eating air. The circular conversations are funny to a point, and yes, the characters know their own narcissism only too well – but the plot goes so round and round, so centred in someone’s head, that it makes you feel dizzy; it’s like being carried along in the clouds, desperately grasping for solid ground.

Like Heti – or, at least, her character within the book – How Should a Person Be? tries to do and say too much. It’s a play within a book, it’s Sheila but not really Sheila, some of it really happened and some didn’t; it’s a book about her and it’s a book about all of us. It’s an experience to read, it’s perceptive, it reflects what it’s like to be endlessly searching to make sense of your presence in the world. It’s often invigorating but also infuriating and, like its characters, lacks any real sense of purpose.

– See more at: http://www.nudgemenow.com/article/person-sheila-heti/#sthash.1EPUQa9z.dpuf

It’s been three days since I finished How Should a Person Be? and I’m still not sure how I feel about it. Like a modern-day On the Road, it’s sprawling and playful, expressing the hopefulness, creativity and uncertainty of today’s urban twenty and thirty-somethings. I’m not sure it’s great writing. But does it matter?

Heti’s book is a tapestry of different forms, a fictionalised account of real life. Into a first-person narrative she weaves emails between her and her friends and transcripts of their long, meandering musings on life and art. Within the book, other art forms are being created and dissected, from the play Heti is struggling to write to the art work created by her close friend, Margaux Williamson. It’s a book that asks whether telling a story through art or literature can ever bring meaning to your own life; make you feel more anchored in the world.

It’s also about how we position ourselves, and shape our perception of the world, through our social circles. Heti and her friends, all artists of some kind, are like flints and steel rubbing together, trying to create a spark. The transcripts of their rambling conversations appear unedited (although this may not be the case) and Heti illuminates a wonderfully messy and vibrant world, which occasionally yields what seem to be life-changing moments. There are drugs – “when we took them, we expanded into a thousand pieces” – and there are drunken revelations: “The bar around us became rich and saturated with colour, as if all the molecules in the air were bursting their seams.” However, Heti undercuts this idealism with a wry humour, and often these experiments and encounters turn out to be dead ends. She is particularly scathing about the well-meaning men she meets: encounters which often start off positively but conclude with her realising, with disappointment, that “he was just another man who wanted to teach me something.”

The patchwork approach of the novel reflects Heti’s own chaotic attempts to find direction: as her psychiatrist warns her, “it is the everlasting switching that is the dangerous thing, not what [you] choose.” This would have been an apt warning for the book itself, which is messy and unconventional, sprawling and unconstrained. It can be joyous and bright, but at times it is frustrating and insubstantial, like eating air. The circular conversations are funny to a point, and yes, the characters know their own narcissism only too well – but the plot goes so round and round, so centred in someone’s head, that it makes you feel dizzy; it’s like being carried along in the clouds, desperately grasping for solid ground.

Like Heti – or, at least, her character within the book – How Should a Person Be? tries to do and say too much. It’s a play within a book, it’s Sheila but not really Sheila, some of it really happened and some didn’t; it’s a book about her and it’s a book about all of us. It’s an experience to read, it’s perceptive, it reflects what it’s like to be endlessly searching to make sense of your presence in the world. It’s often invigorating but also infuriating and, like its characters, lacks any real sense of purpose.

– See more at: http://www.nudgemenow.com/article/person-sheila-heti/#sthash.1EPUQa9z.dpuf